Relevancy and Engagement

agclassroom.org/in/

Relevancy and Engagement

agclassroom.org/in/

Lesson Plan

Working Worms

Grade Level

Purpose

Students observe how earthworms speed the decomposition of organic matter and identify how this adds nutrients to the soil that are important for plant growth by constructing worm habitats from milk jugs. Grades 3-5

Estimated Time

Materials Needed

Activity 1: Worm Jug

- Worm Adoption Certificate, 1 per student

- 1 clear plastic gallon milk jug

- 2 plastic plates, 1 with holes

- Gravel

- Bedding mixture: shredded paper, peat moss, grass clippings, vacuum cleaner bag, debris, leaves, dryer lint, etc.

- Water

- Earthworms

- Chopped fruit and vegetable scraps

Activity 2: Ride the Wild Leaf Cycle

- Ride the Wild Leaf Cycle activity sheets A and B, 1 copy per student

Elaborate

Vocabulary

acre: a unit of area equal to 43,560 square feet (about the size of a football field)

castings: the waste produced by worms

cocoon: an earthworm’s egg sac; similar in size and shape to a grape seed

decomposer: an organism that feeds on and breaks down dead plant or animal matter

earthworm: a burrowing annelid worm that lives in the soil

ecology: a branch of science concerned with the relationships between living things and their environment

organic matter: a soil component derived from the decay of once-living organisms like plants and animals

Did You Know?

- In one acre of land, there can be more than a million earthworms.1

- If a worm's skin dries out, it will die.1

- Baby worms are not born. They hatch from cocoons smaller than a grain of rice.1

Background Agricultural Connections

Earthworms are found everywhere on the earth’s surface, except the north and south poles, where it is too cold. They can be so tiny you can’t see them without a microscope, or they can be several feet long. There are thousands of different species of earthworms, and they have many common names, such as orchard worm, rain worm, angleworm, red wiggler, night crawler, and field worm.

The earthworm has no head, no eyes, no teeth, and no antennae. Its body is made up of many ring-like segments, each of which has bristles that the worm can extend and retract to help it move through the soil. Earthworms don’t have any lungs either. They breathe through their skin, which has to stay moist so oxygen can pass through. Worms can live for a long time in water, as long as the water has oxygen in it, but they will die if their skin dries out. They can also die if they’re exposed to ultraviolet rays from the sun for too long. Earthworms have both male and female reproductive organs, but their eggs still need to be fertilized by another worm. They lay capsules full of fertilized eggs called cocoons. Depending on the species, their cocoons may contain one to several baby worms. Baby worms look like tiny threads when they first emerge.

The worm is the gardener’s best friend. Night and day, worms burrow through acres of ground, swallowing soil as they go. Inside the soil are tiny bits of plants and animals that they grind up as they eat. Worms can taste what they eat and prefer some foods over others. In experiments worms have demonstrated a preference for carrot leaves over celery and celery over cabbage. While they’re eating, a lot of soil passes through the guts of earthworms. Through the process of digestion, nutrients that were locked up in the soil and unavailable to plants or other organisms are released in worms’ waste, which gardeners call castings.

Worm castings are lumps and bumps of soil that come out the back end of a worm. Castings are rich in nutrients such as nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus that help plants grow. The average earthworm will produce its own weight in castings every 24 hours. One earthworm can digest several tons of soil in a year. Not only do castings add nutrients to the soil, but they also improve the soil’s ability to hold water, another bonus for plants. As worms burrow and tunnel, they aerate the soil, providing a looser structure and openings for roots to grow. Their tunnels provide channels for water to enter the soil and improve drainage. Worms are like small rototillers and bags of fertilizer in a very small, and somewhat slimy, package.

Worms are also like nature’s recyclers. We are part of a living and dying world. Plants and animals are born, grow old, and die. Other plants and animals take their places. As each living thing dies, it decays and returns to the soil. One plant’s death may make it possible for new plants to grow where they could not grow before. Worms help speed this process by eating living and dead plant material, digesting it, and depositing it back in the soil as nutrient- rich castings. The relationships between plants, soil organisms like worms, and their environment is known as ecology.

Leaves that fall to the ground in the autumn are a very important part of the forest ecology, or nutrient cycle. The leaves lie on top of others that fell in previous years. This is called forest litter, and it is made up of organic matter. Winter rains and snows keep the leaves wet so decomposers like worms can do their work. There are many different organisms living under the piles of leaves in the dirt that work as decomposers. Some of them are so tiny you can’t see them without a microscope. You are seeing thousands of decomposers all massed together when you see fungi or mold. Decomposers release nutrients from the dead leaves into the soil. In the spring, new plants use those nutrients to grow new leaves.

The process of leaf decomposition on the forest floor is similar to the process of decomposition that happens in a gardener’s compost. Decomposers make healthy soils in natural ecosystems and in the gardens and farms where our food is grown.

Engage

- Inform your students that you will be giving them a list of facts about one specific thing. Ask them to raise their hand when they think they know what you are talking about.

- Use the following clues2:

- They aerate the ground.

- They are vital to soil health.

- They can eat up to 1/3 of their body weight per day!

- They are a source of food for animals like birds, rats, and toads.

- They are typically only a few inches long.

- They are capable of digging as deep as 6.5 feet.

- They are commonly used as fishing bait.

- They can also be known as "night crawlers" because they can be seen feeding above ground at night.

- What is it? A worm!

Explore and Explain

Activity 1: Worm Jug

- Before you begin, share the Background Agricultural Connections information with students and have them each fill out a Worm Adoption Certificate. This will help cut down on creature cruelty and other discipline problems.

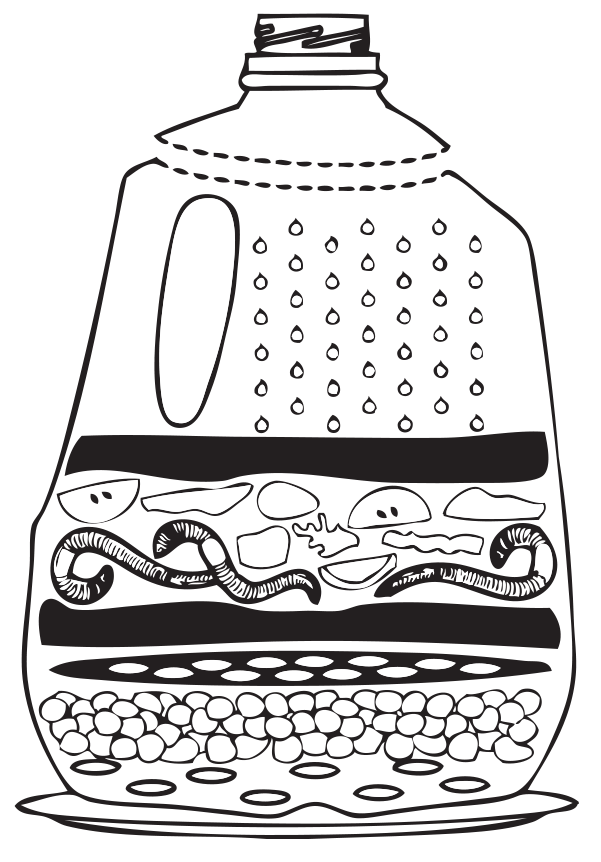

- Cut the top from a clean, clear plastic gallon jug (you will want to do this for the students). Poke holes for drainage in the bottom of the jug. Make sure you have a plastic plate under the jug to collect excess water. Poke small holes in the side of the jug for air flow

- Add 1 inch of gravel for drainage. If you provide shredded newspapers and carefully watch the moisture content in the worm jug, you can omit the gravel.

Poke holes in a plastic lid or plate and place over the gravel.

Poke holes in a plastic lid or plate and place over the gravel.- Add 1 inch of bedding mixture on top of the plate.

- Add a few earthworms.

- Sprinkle some fruit and vegetable scraps on top of the worms. Chopping food scraps in a blender will make them easier for the worms to eat. If a blender is not available, use a knife and cutting board or scissors to cut the scraps into small pieces.

- Cover with more bedding material. Sprinkle with water or spritz with a spray bottle. Make sure bedding is moist, but don’t soak!

- Stir and observe daily. Record what you see in a daily log. Sprinkle with water and add food as needed. Store in a dark location.

- Discuss the following questions:

- Will the population of your worms increase or decrease?

- Are there certain foods the worms like better than the others?

- How long does it take for the worms to eat their food?

- Why are worms good for gardeners?

Activity 2: Ride the Wild Leaf Cycle

- Share the background information about decomposers with students. Explain that worms play an important role in many ecosystems. In garden and farm ecosystems, worms aerate the soil and help release nutrients to crop plants. In forest ecosystems, worms work with other decomposers to break down leaf litter, releasing nutrients to trees and other plants.

- Hand out the Ride the Wild Leaf Cycle activity sheets.

- Have students read about the leaf cycle on activity sheet A and look at the picture on activity sheet B.

- Instruct students to color their activity sheets, then cut out the leaves on sheet A, and glue them over the appropriate number on sheet B.

Elaborate

-

Use the Make Your Own Worm Bin instructions to create a classroom vermicomposting bin out of a recycled styrofoam cooler. Prepare the cooler ahead of time, and then have students add the bedding, worms, and vegetable scraps. Vermicomposting in your classroom is an effective way to engage students with a wide variety of science concepts. For more information about using the worm bin to investigate ecosystems, life and nutrient cycles, and decomposition, see the lesson Vermicomposting (Grades 3-5).

-

View the Vermicomposting Time-lapse video to observe red wriggler worms over 100 days in three composting chambers—leaves, cardboard, and paper.

Sources

Acknowledgements

Background and Activity 1 written by Debra Speilmaker of Utah AITC. Activity 2 written by Pat Thompson of Oklahoma AITC.

Recommended Companion Resources

- Backyard Detective: Critters Up Close

- Compost Stew

- Compost by Gosh!

- Composting: Nature's Recyclers

- Construct a Compost Bottle

- Diary of a Worm

- Dirt: Secrets in the Soil (DVD)

- EIEIO: How Old MacDonald Got His Farm

- Farmer Will Allen and the Growing Table

- How Do You Grow a Fish Sandwich? Video

- In the Garden: Who's Been Here

- Inside the Compost Bin

- Leaf Litter Critters

- Life in a Bucket of Soil

- Lily's Garden

- Make Your Own Worm Bin

- Rotten Pumpkin: A Rotten Tale in 15 Voices

- The Magic School Bus Meets the Rot Squad: A Book About Decomposition

- Up in the Garden and Down in the Dirt

- We Dig Worms!

- Wiggling Worms at Work

- Worm Farm

- Worm Makes a Sandwich

- Worms Eat My Garbage